The tail end of July always rekindles my dream of flying.

I grew up 60 miles due south of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and this time every year the traffic overhead would pick up dramatically as pilots of small sport and experimental aircraft began making their way to the huge Experimental Aircraft Association Fly-In there. All kinds of strange little craft would pass buzzing over my parents' house after stopping to rest and refuel in Hartford or West Bend. But it was the warbirds, the roaring World War II-era fighters and occasional bomber, that would freeze me in my tracks, awestruck, staring skyward like some extra in a Steven Spielberg movie.

I never shook that fascination and continue to find myself drawn to books by or about pilots. Having read plenty, I notice a definite theme emerging in the life stories of former military pilots. Many—if not most—military pilots turn out to have volunteered not out of patriotic fervor, penchant for destruction or family tradition but simply to pursue their dream of flying. Of that number, no few wrestle with their conscience after coming to realize just how much horror and suffering their planes carry in their bellies or slung beneath their wings.

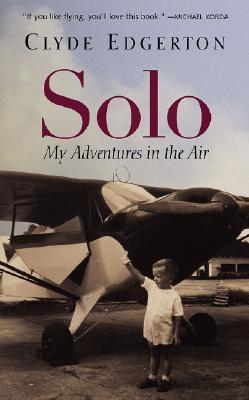

Richard Bach's Bridge across Forever, a New Age hymn to Bach's then-wife actress Leslie Parrish, introduced me to this theme ages ago. For Bach, falling in love with a beautiful antiwar activist at the height of the Vietnam War dulled the hard edge of joy he felt while learning to fly F-4 Phantom fighter-bombers. Clyde Edgerton recounts a similar passage from full-bore enthusiasm to crisis of conscience in Solo: My Adventures in the Air. Edgerton's conscience was pricked not by a beautiful woman but by the evening news and his fellow pilot trainees. All he ever wanted to do is fly (that's a picture of him on the cover), but pursuing that dream during the war in Vietnam involved a kind of moral acrobatics he hadn't anticipated.

A recent book offers a unique twist on this theme. A Higher Call tells the story of German fighter ace Franz Stigler, who escorted a crippled American B-17 bomber out of Germany to the open waters of the North Sea just before Christmas 1943. A civilian pilot before the war, Stigler was drafted into the Luftwaffe as a flight instructor but volunteered for fighter duty after his brother (also a pilot) was killed early in the war. Stigler's recollections of the air war in Africa and the Mediterranean are especially interesting because that theater is so little known in the US and because by all accounts the fighting there was fierce but almost bizarrely chivalrous. (Roald Dahl's delightful Going Solo offers similar testimony but with a wry British accent.) For Stigler, the turn back to his essential nature is gradual, as his desire for vengeance and for glory is exhausted by endless, ultimately hopeless combat.

No comments:

Post a Comment